Thoughts on CEOs & Management Teams

Are CEOs really that important?

Apparently not.

In 2019, Dan Rasmussen of Verdad and Haonan Li wrote an article about the significance of CEOs when it comes to investing in publicly-traded companies.

The main point of the article?

To determine if CEOs really affect stock price performance — and, if so, is that effect persistent or likely random?

They write:

What if CEOs don’t play much of a role in driving stock price performance, and the “aligned incentives” of equity incentive pay don’t change behavior in any way that benefits shareholders?

What if the “best and brightest” — those executives with the most dazzling CVs and track records — don’t perform any better than less credentialed executives?

We often hear so many prominent investors emphasize the importance of “quality management teams.”

But do those quality management teams really make a difference?

The answer is apparently no. According to Rasmussen and Li:

Elite MBA programs do not produce CEOs who perform better than the average.

CEOs with investment-banking/consulting backgrounds did not do better than the average at running companies.

Track records have no bearing on how well a CEO will do in the future.

I found that last point to be striking:

This is not an intuitive finding — and academic studies suggest that this is not how boards think, particularly when it comes to firing bad performers. A 2015 study found that CEOs are often fired after bad firm performance caused by factors beyond their control, a finding in conflict with the standard economic theory of rational expectations. Boards are far more likely to fire CEOs when the industry is having trouble broadly, attributing to a person what is in fact an exogenous economic shock.

We then looked at CEOs who have run multiple companies to see if their performance at the first company predicted outcomes at the second. Headhunters and corporate boards often look for CEOs with a track record of creating value at another company when choosing whom to hire. But if past performance doesn’t predict future results, then they might be looking at an irrelevant variable.

Mariko Gordon of Daruma Asset Management — featured in Meb Faber’s Invest with the House — has, according to Faber, beaten the benchmark Russell 2000 Index for years. And she certainly subscribes to the cult of the CEO:

In some cases, the catalyst is simply a change in leadership….

For example, Daruma started buying Gardner Denver, which makes industrial compressors and pumps, in late 2008 at around $30 a share after the company hired a new CEO. That CEO happened to be someone who was coming from another company that Daruma had invested in with good success. Gordon figured the CEO could engineer something similar at Gardner Denver. By the end of 2009, it was trading over $30. When the company was taken private in 2013, its stock was trading around $75.

Thus, while one-off investment successes like Gordon’s lend support to the cult of the CEO theory, Rasmussen & Li’s research paints a different picture: CEOs on average do not matter as much as we tend to think they do.

Should investors prefer visionary CEOs?

Berkshire’s 1977 letter to shareholders states:

“It is comforting to be in a business where some mistakes can be made and yet a quite satisfactory overall performance can be achieved.”

In other words, some investors might do well investing in a business with tailwinds that, in spite of management, carry the business forward rather than a business with headwinds that leave little room for errors in execution.

Because CEOs and management teams are transient — CEOs leave, executives retire, people die eventually — long-term investors might want to allocate capital to businesses that are hard to mess up no matter who is in charge.

Some companies depend on creative minds, technical talent, and smart management to generate persistent success over decades. Some don’t. The latter are probably more resilient businesses.

A good question to ask when considering an investment is, “does this company depend on management talent (i.e. particular people) to create value?”

Does Altria depend on its CEO to get people to buy cigarettes, or do nicotine, brand loyalty, and a government-mandated anticompetitive market do the job for him? Probably the latter.

Does Facebook need Zuckerberg, or can it rely on the addictive nature of social media to fuel growth? Both are probably important here.

Could Disney have transformed itself into a streaming giant without Bob Iger’s vision and ability to execute some of the most successful media acquisitions in history? Probably not.

Don’t count on successful CEO succession.

It’s true that visionary CEOs and their management teams can, in many instances, bring about outstanding returns for shareholders. Bill Gates, Tim Cook, Satya Nadella, Mark Zuckerberg, and so many others are prime examples.

But that does not mean that investors can reasonably expect companies to consistently identify and hire A+ CEOs and management teams decade after decade. Many fantastic CEOs are followed by mediocre successors (and vice-versa). As a result, business operations and capital allocation might falter from time to time, for extended periods of time.

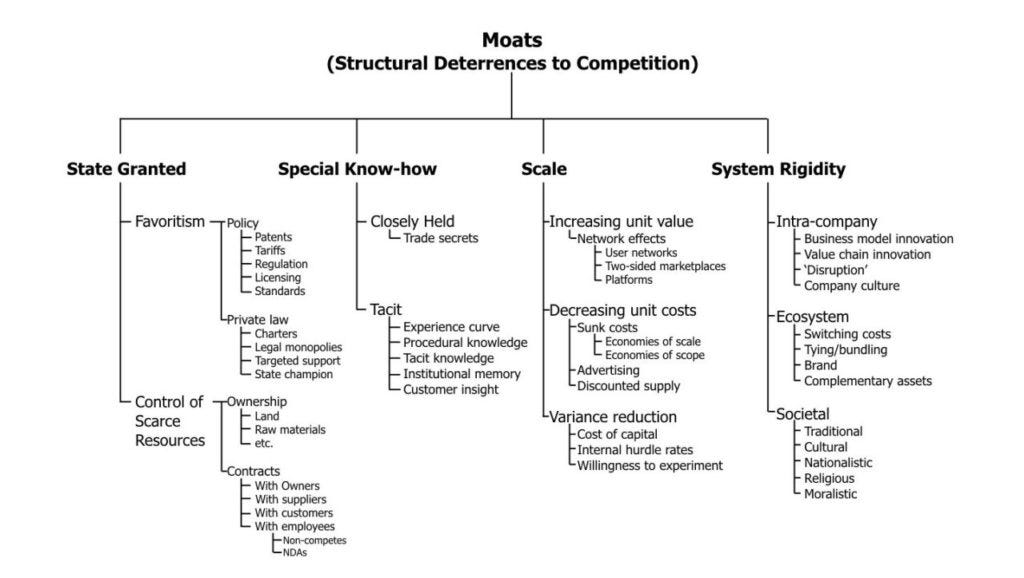

So if you’re planning on holding onto a company for the long haul, relying on a string of outstanding CEOs might not be the best strategy. Legal monopolies, brands, scale, network effects, trade secrets, and industry tailwinds might be more important factors than who’s in charge.

NOTE - Nothing in this newsletter is investment advice. Nothing in this newsletter should be considered an invitation or solicitation to buy any security. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this article. Any assumptions, opinions, and estimates expressed in this article constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Price to Wealth is not acting as your financial, accounting, tax, investment, or other adviser or in any fiduciary capacity.